LIMINAL SPACE

Bridging the In-Between – a transformative documentation of Liminal Space

Contribution by Jonathan Zwiessler

© Luca Weste

Location

Bolzano

Period

2021

Abstract

During the last few years the tag “liminal space” gained more and more popularity in social networks as well as the cultural sector. In an urban context the term describes a space that is in transition and lacks an assigned function or identity.

The question of how to intervene in liminal spaces is often discussed among architects, urban planners, as well as socially engaged artists and designers. Projects frequently claim to develop democratic strategies and methodologies for carefully transforming these spaces. But rarely are those top-down approaches sensible towards the already existing habitats they invade. This has many reasons like for example the institutional frameworks such projects are mostly embedded in and that makes them conform to a variety of rules and regulations. But it is exactly the eclipse of those rules that provides precarious living conditions for different vulnerable groups of people who are excluded from any other places. Therefore it is important to ask who benefits from putting a non-place on the map and who is losing a habitat through the rising popularity of displaying the liminal space.

Not negating that there are great examples of strategies that have created diverse and dynamic situations, this article presents a project that follows a more “tactical” approach. Contrary to the “strategical”, Michel De Certeau describes the tactical as something “that insinuates itself into the other’s place, fragmentarily, without taking it over in its entirety, without being able to keep it at a distance.”

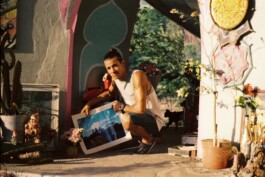

This article is based on an interview with the photographer Luca Weste who documented a public art project that was created through the everyday habits of a man, called Maradona living illegally under a highway bridge in northern Italy. Luca did not only take photographs but formed a temporary support structure for his friend Maradona who he had met years ago. Through the interview, I want to highlight how interwoven the role of a photographer (artist, designer...) can be with individual inhabitants of a liminal space. Thus how this entanglement creates responsibilities and challenges that urbanist strategies cannot really foresee nor solve from a global perspective. By combining different roles like the photographer, the social worker, the publisher, and the journalist and never being able to establish a “professional distance” to his friend, Luca challenged conventional dialogues dealing with the liminal space.

(c) Luca Weste

(c) Luca Weste

(c) Luca Weste

(c) Luca Weste

(c) Luca Weste

Interview

Jonathan Zwiessler in conversation with the photographer Luca Weste, January 2025.

Your work takes place in a so-called ‘non-place’ or ‘liminal space’. How did you become aware of them and do you have any idea why photographing such places has become such a trend on social media lately?

Well, I think it has a lot to do with nostalgia. When I look at pictures on social media with the hashtag ‘liminal space’, they often have references or details that are somehow related to the person’s childhood. These images often play with childhood memories, yes. This is reflected in the retro filters, but also in the way these images are made. They often appear romantic or melancholic. Nevertheless, I also ask myself what exactly links this childhood feeling with the ‘liminal space’, I mean, these are not old childhood photos or most of these people have never seen the place, but they photograph it as if they had seen it many times or a long time ago. So many young people feel nostalgia for things they have never experienced. The American author and neologist John König calls that feeling ‘anemoia.’

Let’s move on to this ‘liminal space’ that you photographed and the person who designed it, Maradona. Can you describe a bit about how it all started and how you and Maradona got to know each other, as well as the place?

I had somehow heard about this place under the big motorway bridge that runs through Bolzano and that someone had decorated and embellished it. So I was curious and went there, but I still had no idea who was behind this work of art. That was in 2021, and it was only later that I found out that someone lives in this place and that this person is also the artist. A few months later, I moved house and from then on, the bridge was always on my way home. So I passed it almost every day. At some point I approached Maradona and from then on we always said hello to each other, but it wasn’t about a project, it was more like neighbourly chats. He also made coffee for me on his camping cooker from time to time. Of course, I was delighted with this place that Maradona had created for the community. He collected the rubbish, kept the place clean, he really took care of it. At some point I asked if I could take a few photos, but that was only with my little analogue camera. But that was all. In the time that followed, we often saw each other there, I brought coffee powder and Maradona made a moka.

Was there a point at which you realised that you would like to do a project about this place? How did you realise that?

Yes, I had studied a lot about the Third Landscape at university and of course Maradona’s place came to mind. But right from the start I was aware of these tensions between institution-non-place, friend-observer... So I approached it very carefully and the friendship with Maradona always came first. But yes, somehow I wanted to tell the story of Maradona and the bridge to more people. How do you do that in a professional way? I don’t know, I think it was more fun for me and I did it as a friend. But how you document a person and his surroundings in a respectful way as a professional photographer is still a mystery to me. I imagine it’s difficult to invest so much time when you work ‘professionally’.

You knew Maradona quite well and his precarious circumstances were visible to you, so why did you decide to leave that part out and just show his art and him as a happy person?

That’s his attitude: he manages to remain optimistic even though he has experienced for himself how difficult life can be. He has lived nomadically for the last twenty years, in various war zones on the African continent, spent weeks waiting in a container on a cargo ship, then arrived on the wrong continent, experienced terrible things there that we can’t even imagine. And yet he shows the world this creative, optimistic side of himself and I wanted to respect that, so you can’t go digging into it because you want to report ‘objectively’ or something. I don’t think that would be very respectful.

Yes, that’s exactly what I mean. I know many photo reportages that tend to focus on the suffering and reduce the people to that. And I think you’ve found a very sensitive way to show Maradona and his art.

The truth is that I’ve thought about it a lot, of course. When am I being too invasive, is this just for our bubble again? What does Maradona gain from me taking photos of his art? I always think that when you do this kind of reportage, even if the intention behind it is good, you have to ask yourself what the people you’re documenting get out of it. I mean directly, what use is it to them? I also got to know other homeless people who live in the area and cooked for them to better understand the situation and then realised how highly complicated each individual situation is. That generalising from one story would be too superficial. At first I also tried to get different perspectives in the traditional way and interviewed the integration officer of Bolzano, for example. But somehow that wasn’t the right approach, so I concentrate fully on Maradona and his project.

But the contact with the politician and your research around it helped you to support Maradona later on, didn’t it?

So it all happened because the winter was very tough, the shelters were overflowing with homeless people and then a 19-year-old froze to death very close to where Maradona was living in a tent. And suddenly everything was so close. And I think Maradona knew the boy because he knew everyone there. In addition, a stranger had started to destroy his artwork. And that’s when Maradona said for the first time that he was no longer safe in that place. Then I started to think about what I could do. And then, through contact with the politician, I was able to find Maradona a temporary place to stay.

And then you initiated this crowdfunding campaign. How did that come about?

Well, Maradona only had this temporary place to stay and although he worked a lot (underpaid), he wasn’t able to put down a deposit, so he couldn’t find a flat. My photos were now on display at ‘Studio Lungomare’ and so Maradona was no longer a stranger. Quite a lot of people already knew the place under the bridge, but didn’t know who was behind it. And then I think it helped that I contacted ‘Lungomare’ and the politician in question and asked her to share my crowdfunding campaign on social media. Because in a relatively short time we had raised the amount for the deposit and a bit more. Thanks to this boost, Maradona still has a flat. Soon he will also have documents and can finally live here officially.

Why do you think Maradona’s aesthetic appealed to so many people? The work of a graffiti artist would probably be perceived differently.

Good question. I think it has to do with the fact that he really made this place more beautiful for everyone and not just for himself. His intention was to create a community space. That’s not what a graffiti artist usually does. So don’t get me wrong (laughs), I’m pro-graffiti but what Maradona did there is somehow different - it’s a more peaceful way of rebelling. I find it incredibly inspiring to see him working there. You know, we’ve been studying interior design for years and he just does it. His aesthetic is very personal. Incidentally, pink was his mother’s and grandmother’s favourite colour. His ‘tag’ is a pink Batman sign, I think that says it all.